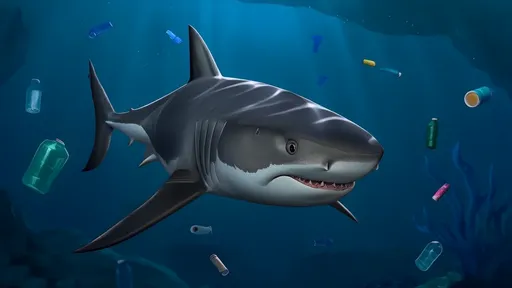

The ocean’s vast expanse hides countless mysteries, but few creatures embody its raw, unfiltered nature quite like the tiger shark. Known as the "garbage can of the sea," this apex predator thrives on an indiscriminate diet, consuming everything from sea turtles to license plates. Its reputation as a scavenger of the deep is both a testament to its adaptability and a grim reflection of human impact on marine ecosystems. Unlike other sharks that specialize in specific prey, the tiger shark’s culinary curiosity makes it a fascinating—and fearsome—force beneath the waves.

The tiger shark’s scientific name, Galeocerdo cuvier, hints at its predatory prowess. "Galeocerdo" translates to "sharp-toothed weasel," a nod to its serrated teeth and relentless hunting style. Found in tropical and temperate waters worldwide, these sharks are easily identified by their dark stripes, which fade as they age. But what truly sets them apart is their stomach contents. Researchers have documented tiger sharks ingesting birds, tires, and even intact suits of armor. This ability to eat almost anything has earned them a unique place in marine biology—and a grim nickname.

While their eating habits might seem bizarre, they reveal a critical survival strategy. In the unpredictable world of the open ocean, food sources can be scarce or sporadic. The tiger shark’s willingness to consume carrion, garbage, or live prey gives it an edge over more finicky predators. Its powerful jaws, capable of crushing turtle shells, allow it to exploit resources other sharks ignore. This adaptability has made it one of the ocean’s most resilient species, but it also exposes the shark to hidden dangers. Plastic waste, fishing gear, and toxic chemicals often end up in its stomach, turning its survival tactic into a deadly liability.

The tiger shark’s role as an apex predator also shapes entire ecosystems. By targeting weak or sick animals, it helps maintain healthy fish populations. Its scavenging habits clean the ocean floor, preventing the buildup of decaying matter. Yet this ecological service comes at a cost. As ocean pollution worsens, tiger sharks increasingly mistake plastic for food. A 2021 study found microplastics in over 80% of tiger shark specimens examined. Unlike bones or shells, plastic doesn’t break down, causing internal blockages or leaching toxins into the shark’s bloodstream.

Human encounters with tiger sharks are rare but often sensationalized. Their size—adults can reach 18 feet—and curiosity make them potential threats, though attacks are statistically insignificant compared to drownings or lightning strikes. Most incidents occur when the shark mistakes a swimmer or surfer for prey. Despite their fearsome reputation, tiger sharks are far more vulnerable to humans than vice versa. Overfishing for their fins, meat, and liver oil has decimated populations in some regions. Their slow reproductive rate—females give birth to just 10-80 pups every three years—makes recovery difficult.

Conservation efforts face unique challenges with this species. Unlike migratory whales or photogenic dolphins, tiger sharks inspire less public sympathy. Their image as "man-eaters" overshadows their ecological importance. Yet some progress is being made. Marine protected areas and fishing regulations have stabilized certain populations. Public awareness campaigns highlight their role in keeping oceans clean—after all, a shark that eats garbage is arguably doing humans a favor. Scientists now use satellite tagging to study their migration patterns, revealing how they connect disparate marine habitats.

The tiger shark’s future hinges on a delicate balance. As climate change alters ocean temperatures and currents, their hunting grounds may shift. Warmer waters could expand their range, but acidification might disrupt prey populations. Meanwhile, the very trait that makes them resilient—their willingness to eat anything—now threatens their survival. Each piece of plastic ingested is a gamble; will it pass harmlessly, or will it kill the shark slowly from within? The answer could determine whether this "garbage can of the sea" continues to reign—or becomes another casualty of human negligence.

Perhaps the most striking irony lies in the tiger shark’s relationship with waste. For millions of years, its digestive system evolved to handle nature’s debris: bones, shells, rotting flesh. But evolution couldn’t anticipate soda cans and nylon ropes. In consuming our trash, the tiger shark holds up a mirror to our throwaway culture. Its stomach contents read like a manifest of human carelessness—a stark reminder that the ocean’s most fearless scavenger is no match for the tide of pollution we’ve unleashed.

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025

By /Jun 11, 2025